ESP member Dr. Bulat K.Yessekin, a senior expert on water, environment and climate change and also The National Coordinator on sustainable development of Kazakhstan for UN from 1998 to 2012 has recently written the following report titled “SDGs: What’s wrong and what do we need to change”.

SDGs: What’s wrong and what do we need to change

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in 2015 at the UN level are today the global community’s response to the challenges that humanity’s facing in the 21st century, including poverty, diseases and environmental degradation. 17 SDGs and 169 tasks have replaced the previous 8 Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were adopted in 2000 upon the initiative of developed countries as the basis for official assistance to developing countries. Today, almost all countries have pledged to adopt programs to achieve the SDGs by 2030.

Over the past 5 years, countries and international organizations have prepared many reports on the implementation of the SDGs, as well as forecasts and recommendations for the future. At the same time, many experts express doubts about the attainability of the SDGs for a number of reasons.

- Voluntary implementation of SDG commitments. The non-binding of UN decisions is related to the status of the UN organizations that are politically and financially dependent on governments. In addition to the recommendatory nature, the principle of consensus in UN decision-making leads to the fact that professional proposals of experts pass through a sieve of political editing with amendments made by governments and influential organizations. As a result, many decisions are distorted or blurred. For the same reasons, the SDGs today do not include such fundamental goals as the human and wildlife rights. Many countries do not consider the SDGs obligatory, do not allocate special budgets for them, and using updated terminology keep pursuing their old strategies based on economic growth, to the detriment of overall global and regional goals. The SDGs remain in the form of virtual programs without the necessary status and funding. The community, business, academia and the local authorities also remain alienated observers in this process (they do not perceive the SDGs as personal goals).

- UN methodology of assessing SDGs. The UN and its partners have prepared a set of guidelines to help countries organize the work on SDGs and measure progress. In voluntary national reports (VNRs), many countries, combining statistics and indicators, try to show progress in meeting international obligations. But in reality, such progress is often absent: physical (non-monetary) indicators evidence the opposite. At the same time, instead of reports clearly show on the achievement of goals, the information on the “coverage” of goals is provided, which does not mean their implementation. For example, in its VNR (2019)[1] the government of Kazakhstan showed that almost 90% of the goals on water and sanitation (SDG-6) are covered (and 100% of the goals for health, hunger, sustainable energy, cities, education and industry). At the same time, an independent assessment shows that problems related to water resources in the country are only growing and water management (SDG6.5) is getting worse every year (an independent assessment of this goal showed only 30%[2] of coverage). The main drawback of the methodology proposed by the UN to governments is that it is based (with all the references to participation and involvement) on the assessments of the states of their own work and then the discussion with experts and the public[3]. It would be correct to do the opposite: first, an independent expert assessment with the participation of the public should be made, and only then it should be discussed with government agencies, which would make it possible not to hide, but to identify and solve problems in a timely manner. In some countries, independent public assessments of the implementation of the SDGs are also carried out, but they are made either in a parallel way or after the completion of official reports and therefore have little impact on their content.

- Status and content of the SDGs. According to the decisions taken, all 17 SDGs have an equilibrium status, which is also a consequence of political consensus between countries (as well as international organizations’ lobbying for many goals, and particularly in the interests of future funding). However, it is clear that the SDGs are not homogeneous and have different status: many of them are consequences or causes for other goals or means of achieving them. For example, health is mainly a consequence of the environmental conditions, income, or education. Or the Goal 6.5 (water management) is not a goal itself, but a means to preserve aquatic ecosystems and sustainable water supply. Unclear links between the SDGs allow countries, governmental, international and other organizations, with all the claims of synergy, to continue to act autonomously, juggling convenient SDGs and competing for resources. With that, some of the SDGs are essentially opposite in their essence. For example, such a goal as the one on economic growth (SDG8), which means the quantitative growth of production and consumption, contradicts the goal 12, as well as such goals as climate change (13) and preserving ecosystems (14,15). Such inaccuracies and contradictions within the SDGs give countries false guidance and overshadow the most important and urgent goals. A multi-storey building with prosperous and disadvantaged residents, friendly or conflicting neighbors is the analogy. But it is obvious that problems with shared foundation and roof should take precedence over others, including such problems as poverty, energy, gender inequality and others that are important for many countries, but not for all. In the context of the growing environmental crisis, countries are forced to single out SDGs with highest priority from the entire list of SDGs. For example, developed countries are significantly increasing their commitments and creating enforcement mechanisms for other countries (for example, the EU carbon border tax) on the global problem of climate change. However, on other important tasks, for example, on the protection of ecosystems and biodiversity – the basic condition for the life on the planet, there are still no such understanding and actions.

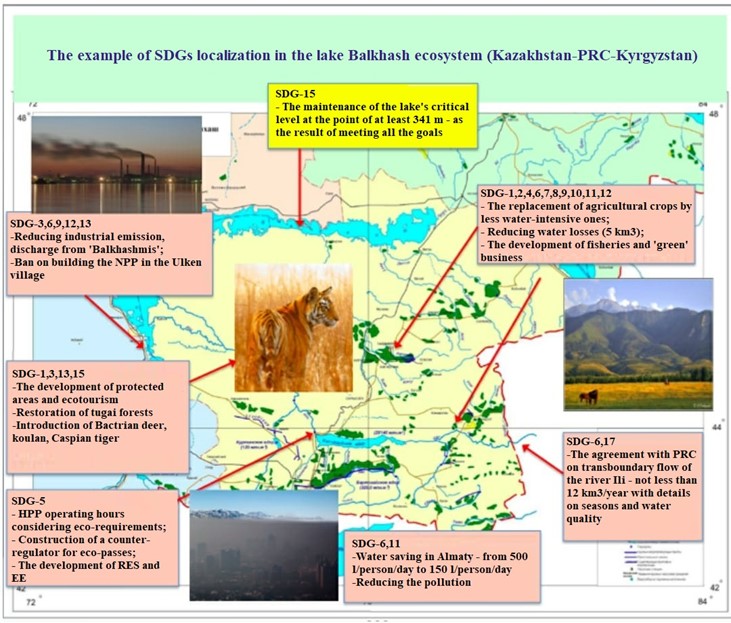

- Localization of the SDGs. The equal status of all SDGs is a consequence of not only the UN decision-making system, but also the lack of their localization – binding to the territory. None of the SDGs are geographically specific. This was supposed to be done at the countries level. But at the national level, countries, following the UN approach, form their national programs according to a sectoral-resource principle, which enables them to demonstrate the implementation of the SDGs without changing their ongoing policies that undermine the foundations of sustainable development. Localizing the SDGs requires revising and adjusting national goals and strategies, making commitments and taking responsibility to the regions and the community. For example, in Kazakhstan, the goals to achieve a 50% of sustainable energy sources in the total energy production or a 50% reduction in energy efficiency by 2050 without localization do not have their quantitative justification (is it enough or not?). Moreover, these goals are not distributed between sectoral and territorial entities, which makes them obviously impracticable. The reports of the Kazakhstan government on the SDGs represent general information on separate projects or initiatives carried out within the country and do not practically affect the main programs and the interests of the private sector in the sustaining of coal, oil and other carbon-intensive and “brown” strategies. Without localizing the SDGs, international organizations (UN, EU and others), as well as countries, demonstrate complicated pictures about their interconnections:

- Sectoral and resource management approach, lack of ecosystem management. Today, a sectoral and resource-based approach is still used in planning programs and projects at all levels – from the global to the local, which ultimately leads to the opposite results, worsening both the quality of life and environmental sustainability. As a result of sectoral and administrative-territorial planning in the state programs and plans of Kazakhstan, known to be extremely vulnerable due to the arid climate and lack of access to the world ocean by aquatic ecosystems, there are no goals for the preservation of aquatic ecosystems – the basis for sustainable water supply for the economy, the public and the natural environment. In an economy focused on maximizing the use of natural resources, such goals are not much needed – they are replaced by goals on increasing production and consumption, dams and weirs that destroy the natural basis of the economy and ultimately impede all the SDGs. The same approach to other programs: for the development of cities and industrial centers, the emphasis is concentrated on costly measures – the construction of new coal power plants and nuclear power plants (instead of the development of renewables and energy efficiency), the expansion of roads and parking lots (to the detriment of public areas). With that, the most dangerous pollutions are not included in the number of main goals – they have the informational status (e.g. MPC), without purposeful actions and responsibility for their achievement.

The full implementation of the ecosystem approach requires a different management system, and the localization of SDGs based on ecosystems makes it possible to establish exact and reasonable values for all the goals and gives a clear understanding of how exactly the various sectoral goals (water, energy, food, poverty, education, etc.) are logically, spatially and quantitatively interconnected. It creates the basis for the full integration of the actions of various economic players. As in the human body, where all the vital systems are interconnected and have precise parameters that are important for life and health, the localization of goals must be taken not within administrative boundaries, but on the basis of natural ecosystems, indivisible into administrative boundaries, taking into account a complex but stable system of connections between wildlife and all environmental components. Only with this approach, the goals and actions of various economic programs, conflicting in the current management systems because of their imaginary independence, will take their place in the common system of natural and technological processes and create synergy to achieve the SDGs. The ecosystem approach also allows for the integration of public health objectives related to the disruption of the natural balance in order to avoid future pandemics.

For the Kazakhstan conditions (as for many other countries), management should be based on ecosystems of river basins, representing integral natural complexes covering the entire territory of the country, the state of which is the basis and the main limiting factor for economic and social development. An example of localizing SDGs based on an ecosystem approach in the Balkhash-Alakol basin is shown below.

The example of localizing SDGs based on an ecosystem approach

The Balkhash-Alakol basin is proposed as a model for transforming of the long-standing problems into opportunities for sustainable development. The basin is one of the world’s largest lake ecosystems with an area of 512 thousand km2 – more than GB, Holland, Denmark, Switzerland and Belgium all together.

As the entire and indivisible system, it is an integral organism with its population, industries, water, land, and mineral, biological and other resources, transport, and energy and tourism infrastructure. At the same time, Lake Balkhash itself plays the role of a unique and irreplaceable natural regulator of ecological balance, supporting the life of more than 50,000 rivers, lakes and watercourses that regulate the climate and support biodiversity and provide water to industry, population and agriculture, energy facilities and public utilities. The basin contains 12 types of ecosystems (from glaciers to deserts), reserved areas and natural parks – with the territory of more than 4,000 km2, including the state nature reserved area and the state forest, farmland and pastures – with the territory of more than 23.0 million hectares. The unused potential for a green economy in this basin includes renewable energy (more than 500 MW), shipping (55,000 tons of cargo/year), fisheries with a potential of more than 53,000 tons of fish products/year, sustainable tourism and others. At the same time, the lake itself plays a fundamental role in the natural cycle of the exchange of energy and substances, evaporation and precipitation, the flow of water over the surface and underground.

At the same time, due to the lack of integral ecosystem management, the basin continues to degrade: there are only 5 out of 16 lake systems remained, more than 150,000 km2 are deserted. According to McKinsey estimation, water deficit in the basin may reach 1.9 billion m[4] by 2030 as the result of current development, transboundary water abstraction and climate change, which will cause irreversible degradation of the entire ecosystem with growing economic damage and social consequences similar to the disaster of the Aral Sea.

However, the lessons have not been learned: the current state program for water resources management in Kazakhstan repeats previous approaches and does not set the main goal of preserving this vulnerable ecosystem as an indispensable and key condition for sustainable development of this region. The program is focused mainly on the goals of economic growth: an increase in the area of irrigated land and the construction of new reservoirs, with an increase in budgetary expenditures and the loss of the very possibility of saving this unique ecosystem, on which the well-being of millions of people who live there depends.

With all the understanding of this problem and undeniable arguments, the government is not ready to change the management, while maintaining their destructive resource-based approach. At the same time, the transition to ecosystem management will make it possible to stop growing environmental threats, adjust existing programs, clarify the links between all stakeholders and identify actions that are important not only for preserving the natural basis of social well-being and economic development, but also for the sustainability of all the sectoral and territorial programs and private sector projects that are being implemented.

Practical Steps for shifting to Ecosystem Management

Back in 2007, the government of Kazakhstan adopted a resolution based on the recommendations of the EU project on integrated management in the Balkhash-Alakol basin which stated the following: ‘The existing basin’s territory management system based on fragmentary powers and short-term actions does not provide basin’s current problems solution and the territory development, and doesn’t contribute to the consolidation of the actions of central and local authorities, the state, the civil society and the private sector. “One of the main results of the analysis is the conclusion about the need to improve the management system in the Balkhash-Alakol region as a key condition for launching and implementing the program, the transition to integrated planning and management, and the involvement of the existing potential of the region.” The decree instructed “to study the possibilities of introducing ecosystem management on the basis of the basin principle with an international examination of the project called “Regulation on the basin management body”. “In general, the basin management system being formed will set the parameters for further improvement of the administrative-territorial organization of the region and the territory planning system.” Thus, an attempt was made to transition to ecosystem management. But decisions at the governmental level were not enough and more basic changes were required.

With an ecosystem approach in relation to this basin, the current main goal of the state program for providing water to economic needs remains, but will be linked to a higher level goal – the conservation and restoration of lake and river ecosystems, including the protection of water sources and catchment areas, mountain and forest ecosystems, emission, discharge and waste reduction. The integrated sum total of all plans and actions in the basin should be a lake level of at least 341m, which means the maintaining of a balance between inflow and discharge of water – the main indicator of all SDGs for this significant region – an indicator of coordinated and sustainable economic activity and social well-being in the basin.

To achieve this goal, it is necessary to solve the three main following tasks:

- Task 1. The guaranteed volume of overland runoff in the basin is at least 25 km3/year;

- Task 2. Agreement with the China on transboundary flow – not less than 12 km3/year;

- Task 3. Ecological runoff for the delta (not less than for evaporation) -14,5 km3/year.

Each task will require correction of all goals and programs in various sectors of the economy: agriculture and public utilities, energy, industry and other sectors – with reasonable quantitative and interrelated indicators, e.g.:

- In agriculture: reducing water losses and replacing water-intensive crops, including rice, on an area of at least 25,000 hectares (it will also require targeted support from farmers), prohibiting the expansion of irrigated land without guaranteed water resources;

- In industry: reducing emissions and stopping discharges (with a package of a new green standards and technologies, economic and other instruments);

- In the energy sector: changing and adjusting the operating modes of all HPPs, construction of the Kerbulak counter-regulator to support environmental flow;

- In the communal sector: water saving and reduction of water losses (for example, in Almaty – it is necessary to reduce the consumption from 350-500 to 100-150 l/day/person, including the ban on car wash using drinking water), development of renewable energy sources and other areas of a green economy;

- In nature conservation: restoration of the lake delta, tugai forests and biodiversity, development of eco-tourism, natural parks, reserved areas and the introduction of the Turanian tiger (as an indicator of forest restoration and biodiversity).

Only the holistic management of the above mentioned and other sectoral and territorial programs will ensure the preservation of the ecosystems of the basin for the sustainability of economic activity and social well-being in this large region and support of the global SDGs at the national level.

The world has accumulated various experiences in the transition to ecosystem management. Many countries adopted special laws, for example, in the USA back in the 50s a specific Basin Management Law was adopted to stop sectoral conflicts and halt environmental degradation in the Tennessee Valley. The EU, Canada, Japan and other countries have also adopted laws and special programs and mechanisms to support ecosystem management.

At the same time, successful international experience shows that:

- river basins should be the basis for territorial management as integral and indivisible management objects and for the full integration of sectoral and administrative-territorial programs into sustainable development programs;

- objectives to preserve the ecosystems of the basin as a key condition for sustainable economic activity and social development should be prioritized;

- Alienation of the population and nature users from sustainable development programs, territory management, distribution of risks and benefits should be overcome and formalized;

- the basin management body should have the necessary authority and responsibility for the long-term water, land and energy use, infrastructure management, and for attracting investments.

In Kazakhstan, such reforms are possible through the adoption of the “Law on Lake Balkhash” with the main directions and clear objectives of the program, with the creation of an authorized governing body. At the same time, the creation of a basin management working body is a primary and necessary condition for launching such a program. To overcome alienation, market economy failures and fragmented management, transferring conflicts between the state, business and the public into engaged cooperation, it is proposed to create a management in the form of a basin social corporation. Its main difference (from industrial and financial corporations) is that the activities of a social corporation are aimed at integrating social, environmental and commercial effects. With that, long-term environmental and social goals are a priority, and management mechanisms stimulate the development of green sectors of the economy and restrain the desire for profit at any cost – at the expense of the destruction of natural and social potential.

Basin social corporation “Balkhash” as an open joint-stock company with the participation of the public, the state, business and all natural resource users:

- Overcomes alienation, changes the interests and behavior of the private sector and the population for their engaged participation in the common development program;

- Creates a focus on long-term goals and social benefits, including health and education – not only on profit;

- Eliminates social conflicts and unites the actions of the state, business and civil society;

- Is more free to use different form of financing and creates more efficient and transparent mechanisms for sustainable economic activity (income from activities, fees for services, ecosystem payments, loans, etc.);

- Is more efficient in the development of a green technologies and of the basin infrastructure management (dams and power plants, fisheries, irrigation, tourism and other facilities);

- Resolves cross-border conflicts with more effective tools based on a common benefits: translates problems into benefits, taking into account interests of all parties;

- Does not exclude, but complements and helps in the implementation of state, departmental and territorial programs, state control and monitoring systems.

The basin management system will change the ongoing destructive processes. Financing decisions for any programs and projects from state, local budgets and the private sector, as well as new projects in the basin will make the maximum contribution to the achievement of common goals, thereby increasing the sustainability of all sectoral, territorial and business sector programs. The existing systems of planning, monitoring and control, education, information sharing and public participation shall also be improved in the interests of all parties.

The new management model will allow to go beyond the traditional choice at the practical level: «economy or environment» and will open a new perspectives for the population and business. It will provide governments with innovative solutions to achieve the SDGs, develop green economy and sustainable employment, and take control over growing social problems and dependence on climate change, while improving the quality of life and environmental sustainability.

The Covid-19 crisis showed that nature, health, inequality and the economy are interconnected, and that humans are at the center of the development. Kazakhstan can create an innovative model of responsible and wisdom management to avoid serious consequences and to support the global transition to a green economy.

[4] Green economy strategy for Kazakhstan, McKinsey, 2012